In part one I described how Susan and I developed a plan to hunt agates across the American northwest during a long October vacation. I couldn’t say where the idea came from, why agates, or why now? But off we went across the fruited plain with our limited collecting gear and a little knowledge gleaned online in the days before starting. The one site we hunted in Nebraska and the one riverbed in South Dakota were each good to us.

We pulled into a dusty rest area shortly after reaching Montana and photographed the colorful chunks of volcanic material on display there along with fossils. Just ahead, we pulled in at the Powder River to have a quick look before getting on to the Yellowstone River country. Here, we started finding agates, or potential agates, immediately as well as petrified wood. The agates weren’t outwardly colorful or attractive but I was starting to develop an eye for their outer texture and translucence. The agates here were also larger than average, with some probably topping three pounds. After a mere twenty minutes or so of wandering around on the nearest gravel bar, there was a Susan pile and a Cedric pile and we just took the best of what we’d amassed so far. Still, the car was now filling with rocks at an alarming rate. This wouldn’t be the last we’d see of the Powder River. I warned Susan that one of her travel bags might soon have to be left alongside the road to accommodate more stones.

There wasn’t a lot more rock hunting on this particular day and by late afternoon we passed Billings and continued west on I-90, stopping at Columbus, Montana for the night. Here, there was a nice park along the Yellowstone where we walked both in the evening and the next morning before hitting the road. We’d heard about the abundance of agates in the bed of the Yellowstone but were disappointed to find little promising here in the short time we had to look things over. There was a lot of granite and a lot of stuff that looked like sandstone, not so much agate or the closely-related jasper. This wouldn’t be the last we’d see of the Yellowstone.

While on an early-morning run here at Columbus, I got my first look at the northern lights, barely discernible but there they were.

Now we simply spent hours on I-90 heading northwest across central and western Montana, moving up into the Rockies. A bit north of Yellowstone Park, we stopped at Livingston’s Windy Way Rock Shop to browse the merchandise and see if we could get an opinion on the things we really hoped were agates so far.

Here, Barbara, the lady behind the counter, was more than helpful and we spent more time here than we’d imagined spending and garnered several specimens from Windy Way’s shelves. Barbara happily invited me to bring in our own rocks for an opinion and I grabbed a couple of weighty sacks for evaluation. I can only imagine that Barbara was honest, and knowledgeable, but she didn’t tell us what we wanted to hear. She liked to use the word “quartzite” for what I’d felt sure was chalcedony (the basic mineral of agates and jaspers). She tried to explain how you could see this in the rock but it would take a good bit of practice yet for me to really get it. She explained as well that even chalcedony is a form of quartz (as is quartzite, of course).

Yes, we would need more practice with this. Still, I wasn’t ready to empty my bins and bags of quartzite along the road somewhere just yet. And among the rocks she hadn’t inspected, we did already have some treasures. Now we rushed off to the west, with one more daily destination still out on the horizon.

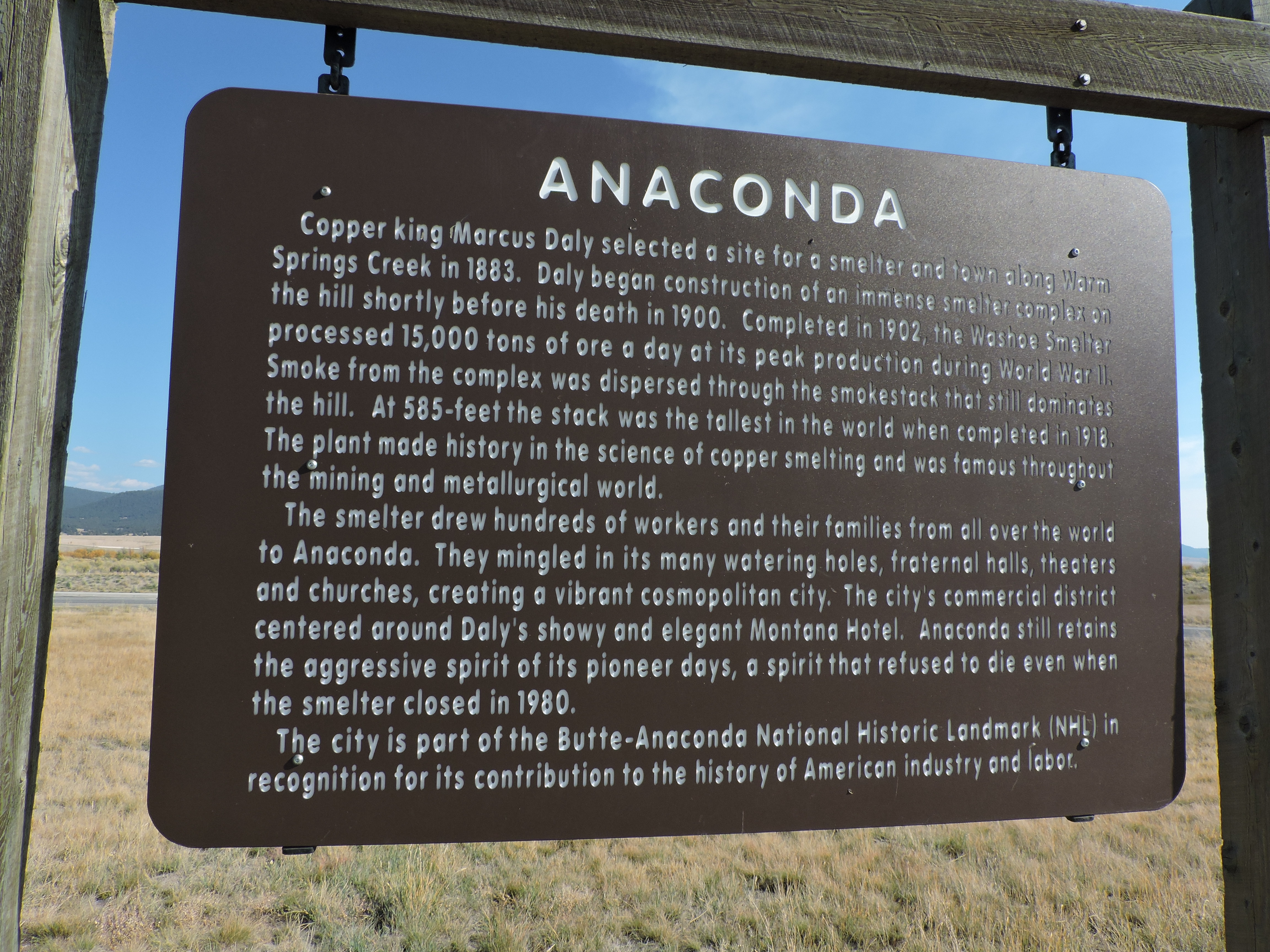

In the area of Anaconda we left the interstate again and began the long climb up to Phillipsburg, a historic mining settlement. Among the several interesting and valuable things mined here over the last century or more were sapphires, a gem that wasn’t a part of the grand agate hunting plan but the facility for tourist sapphire “mining” was just kind of low-hanging fruit and something I imagined Susan might enjoy. We had to try it once but I thought it was to rock hunting what stocked trout fishing was to real fishing.

We arrived at the Gem Mountain facility in downtown Phillipsburg just in time for the last “wash” of the day – there was no-one in line behind us. We then bought a $45 bucket of mud. You might be thinking that Gem Mountain was running a pretty good scam selling such buckets to eager tourists but I thought there just might be a payoff for us as well. So, over the next forty minutes or so, we sloshed and washed and sifted and shook trays of mud and then fine gravel, looking for subdued greenish gleams among the smallest rocks. Sapphires are generally not large. We would be doing well to pocket one of two or three carats.

When all was said and done here, we had about 14 sapphires, including one pink specimen and one pushing two carats. Our stones were evaluated after excavation and we were told, sympathetically, that our finds were generally below what can usually be expected from a bucket of mud here and we were given a free sack of “paydirt” to take home and sift back in Pennsylvania. So, this was alright and we didn’t really leave feeling cheated, especially after finding a large quartz crystal lying along the curb out in the parking lot. We would go back to Gem Mountain, given the opportunity.

We spent the night high in the mountains along the Clark Fork River not too far from the Idaho border. We were still very new to all this and I suspected the best was yet to come for the two agate-hunting heroes from Pennsylvania. We’d been speeding west to this point, really taking only minimal time to look around at the rocks (and the rest of the natural world) but in north-eastern Washington State, we’d slow down and things would get more interesting.

Yes, we’d slow down soon but not just yet. In the morning, we sped over the divide, across the border and downhill into Idaho. Almost immediately, we took the exit for Mullan, Idaho though. At about the beginning of 2024, I’d begun to take an interest in silver, from an investor’s standpoint, and I’d learned a good bit about the metal, perhaps even becoming a bit obsessed with it. During this time, I’d learned that the most productive U.S. mine for the metal, an incredibly deep shaft into the basement rocks of the Rockies, is the Lucky Friday mine of Mullan, Idaho. So, I just wanted to see it. And there wasn’t much more to the stop than that. We saw the mine, we walked a bit on the pedestrian trail and we scooted on west.

Later that day we crossed another border, finally reaching Washington State, and you just can’t drive much further west than Washington State. We circumvented Spokane (not as nice place as it once was) and made for the far northeastern mountains. We made a phone call to alert Dwight that we were on track.

Now, we would slow down, enjoy good company, participate in some exploration and ferret out some quality rocks and minerals, I felt sure. Ferrets might or might not be involved.