In parts one and two I described the early days of a long and unusual trip through the American northwest. I’d been here before, in fact I’d walked through all of it once, but I hadn’t paid a lot of attention to the rocks all around me at the time. On this trip, I compensated for that oversight, or over-compensated, now spending nearly a month hunting agates across the states of Nebraska, South Dakota, Montana, Idaho, Washington, etc. At the end of part two, Susan and I were about to arrive at one of the most special destinations along our entire route.

Dwight welcomed us into his home once again despite the transition that was now taking place with his family and log structure he’d crafted with his own hands many years before. I’d been here twice before and Susan once, but it had been a couple of years. Hailing from western Pennsylvania, we can’t just pop over for a cup of tea on a whim. And our rare visits to the northeast Washington forest would surely be incomplete without a guide like Dwight.

Dwight, now over 80, was in process of turning the property over to his daughter and son-in-law and so, with all that was going on, it was certainly generous of him (and them) to put us up for a couple of nights. We met Dwight’s daughter and son-in-law, briefly, as well as each of the several new pets. Needless to say there was simply a lot of introduction and catching-up to do but I was also able to ask Dwight a set of questions I felt were necessary inquiries pertaining to the book I’m now crafting, the one that tells the story of my first meeting with Dwight. I also had a special request to make of Dwight pertaining to our mineralogical ambitions:

“Dwight, you’ve told us how both gold and silver were mined here in the vicinity. It so happens that we’re carrying gold panning equipment this year. So, if you could show us where we can pan up the mother-lode, that would be great.”

The next morning, Dwight did oblige us and we all piled into his car for a ride up into the woods near the Canadian border. We had a little trouble finding a good site, with plenty of access and plenty of gravel, but finally we did find a spot near a bridge which fit the bill. A small but working gold mine could be seen just downstream. And so, we busied ourselves with sifting of material through the classifiers and sloshing, swishing and swirling tiny rock fragments around and around in our pans. It was a first try and we didn’t expect much but we did find, among the heavy material left when everything else had been swished out of the pans, some tiny yellow rocks. And by tiny, I mean approximately sand-size. Sand-size or smaller. None of it was likely gold. But just maybe…

On the way home, Dwight showed us a few old-time silver and gold mines, now just crumbled piles of timbers and perhaps seeps emanating from deep within the earth. These places were just dilapidated remnants of structures that were never meant to please aesthetically in the first place and now were blending again with the mountain forest but it was truly grand to be here in the Washington State wilderness, standing here alongside an actual nineteenth-century western gold mine.

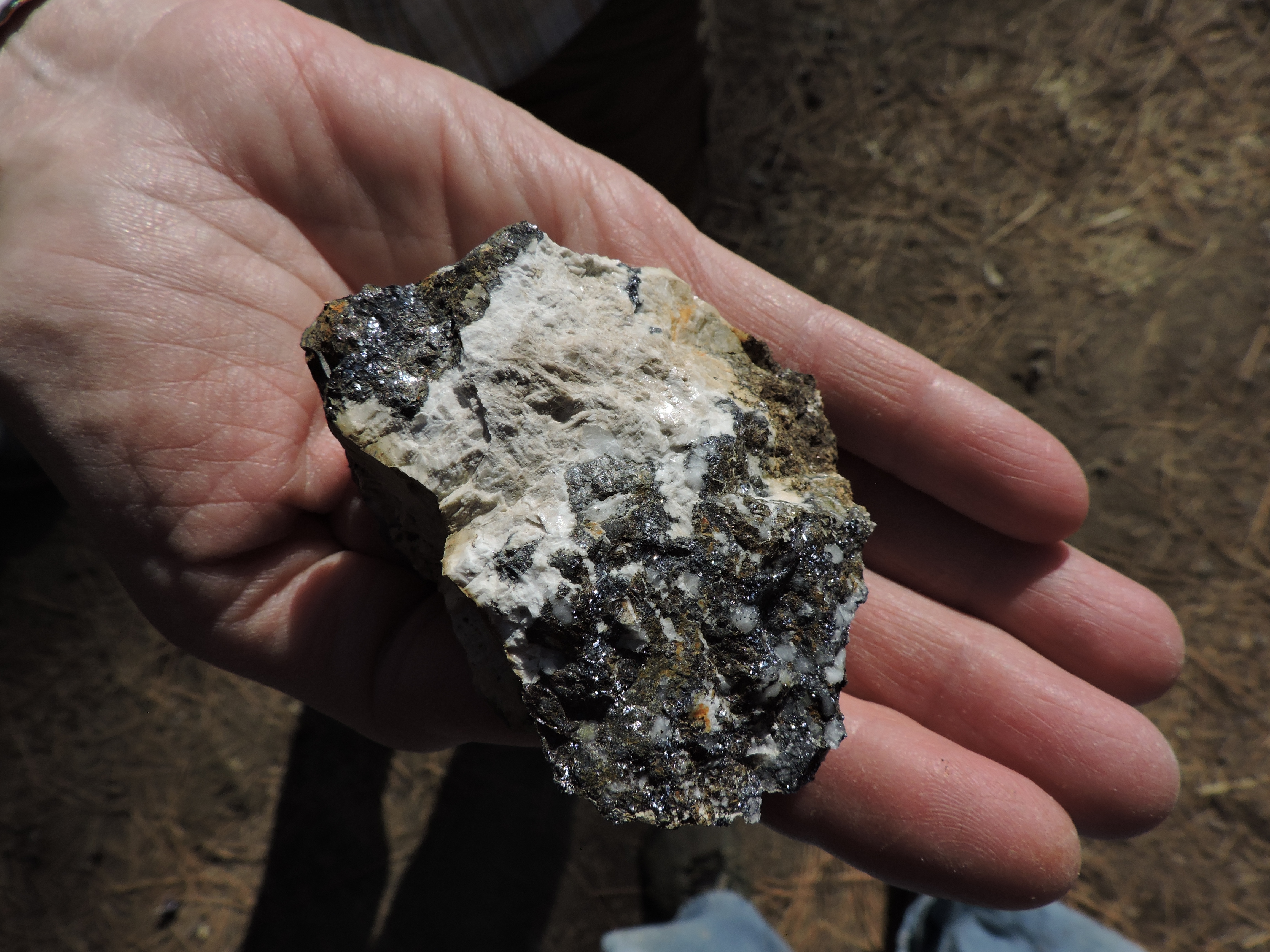

We stopped at Dwight’s own little camp in the woods, a place he’d been putting some work into recently, and admired his craftsmanship. He rolled a small boulder over just alongside the stairs and told us that this chunk of what seemed to be white quartz contained a large amount of silver ore and just a little gold too. He then reached for a hammer and whacked off a corner of this rock, weighing probably a few ounces and handed it to us. Silver sparkled in the afternoon sunlight and we’d just been handed one of the very best stones we’d collect on the entire trip.

Still moving west from Dwight’s, we headed west toward the coast but we were taking our time now and really wanted to see northern Washington. We made brief stops and picked up a few agate-like rocks. We paused at the wilderness outpost of Republic and took a brief look at a dig-your-own-fossils site which was now closed for the season. We continued west into the national forest in the late afternoon and made one more stop to find some of that singularly heavy and valuable precious metal. I had caught the gold fever though Susan’s immunity remained strong.

I picked a stream almost randomly, one being as likely as another to produce in this region, as far as I could tell. I knew already that Susan lacked enthusiasm for the panning so I knew I couldn’t prolong this. We’d have to take a best guess, dig down and scrape the bedrock for a few pans of heavy stuff. The stream looked less than inviting to a panner: too much mud and not enough gravel. But digging down below the rich organic layer, I felt the crunch of gravel and I started digging. Soon Susan was swishing pans as quickly as I could fill them.

Again, we found some yellowish sand grains. They seemed too angular though, and not really heavy enough. I hit the bottom of my second hole and worked a pan myself all the way down through the heavy dark magnetite at the bottom. Something gleamed brightly from the bottom of this pan, something “hot” yellow, a vibrant burst of light in the dim forest understory. “Eureka,” I said to Susan.

We traveled on up and over the Wauconda Pass and on into the Okanogan Valley. I remembered a tough day of walking through here, in the opposite direction. This had been a point at which I’d thought the walk across America was coming to an end due to continued and extreme foot pain. It was already evening as we came along the Okanogan River and then, with just a few scant raindrops falling, we lost sight of our arid surroundings. The rest of the trip up the Methow Valley to Winthrop would be traversed in the dark and in the rain.

Little of minerological significance transpired at Winthrop or the drive on across the mountains to the coast. That is, unless you count the 7,000 + foot stone monoliths of the Cascades as “mineralogical.” Since I’ve been traveling to the west, people have advised over and over that I needed to see the northern Cascades and that this was simply one of the most scenic places in existence. This proved to be true and I think that we couldn’t have picked a finer day on which to see these promontories for the first time. Snow was threatening, and even falling at times, but the road was never more than wet and we were able to view newly snow-draped elephantine peaks as shafts of light passed between the storm clouds. I’d take this over a sunny afternoon any time.

The long slide down to the coast was executed via route 20 along the notoriously tempermental Skagit, a geo-phyle’s dream venue, the kind of place that turns over all of its sediment every year (probably multiple times) and its “sediment” includes boulders weighing tons. There aren’t really rapids here but rather the many miles from Gorge Lake on down seem all one continuous rapid. We stopped and gathered just a handful of rocks that vaguely resembled agates (but probably weren’t). We also stopped to see elk for the first time.

We made our way through the rush hour traffic of Sedro-Wooley and were soon crossing the narrow channel that separates Fidalgo Island from the mainland. Now seagulls were replacing the crows and hawks of earlier in the day and the waters definitely appeared tidal.

Susan chose a hotel room for the night while I pitched a tent in the wilds of Washington Park – the place I’d slept one late March night a few years ago before getting up and walking across the United States. It was good to be back in this mossy forest among the fungi and black-tailed deer. The moon was full and all was quiet but for the owls and gently lull of waves.

So, we spent a couple of days here at Anacortes and I was actually able to hunt agates. There are many devotees of this pursuit here in the extreme northwest, people who hunt the rounded pebbles and beach cobbles for the occasional fine agate and I became one of these people just a little while. And I had a special target in mind here too: the carnelian agate, something we believed we’d already seen once or twice but something particularly prized among the egg-like agates rolling in on the Pacific surf. And it struck me, perhaps as a sea lion surfaced for the first time just out in front of me, that I was now an awfully long way from the three rivers of Pittsburgh.

The two carnelians I found among the jumble high up in the driftwood weren’t really the vivid stones of eye-spot swirls and etherial sanguinary tones. All that would have to wait for the cutting and polishing. But we did have two west coast beach carnelian agates sealed in a bag in the back as we began accelerating back across America.

It had all been good so far but we’d crossed several high mountain ranges as we’d come west and now, late in the season, we needed to cross these again. The now wintery high-elevation weather could be unforgiving above 4,000 feet or so. There were tire chains under the driver’s seat but I really didn’t look forward to using them.